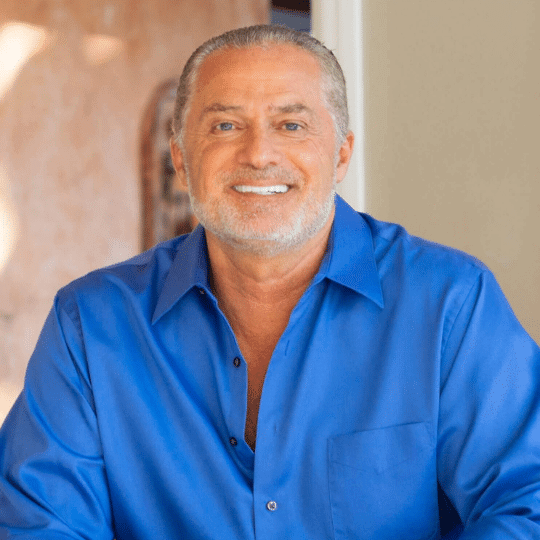

Workforce Leadership Profile: Advancing Equity Through Workforce Development with Clair Minson

For almost twenty years, the Aspen Institute Economic Opportunities Program has convened local and national academies that bring together senior leaders from across the workforce ecosystem to learn together about increasing economic opportunity for all.

In this conversation — facilitated by EOP Senior Fellow Dee Wallace — we hear from Clair Minson, the founder and principal consultant at Sandra Grace LLC, co-director of Workforce Matters, and a 2015 alumna of the Weinberg Sector Skills Academy in Baltimore.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. Explore the full interview on YouTube or subscribe to our podcast to listen on the go and learn more about Clair Minson’s vision for workforce development, her leadership journey across the field, and what role her faith plays in navigating opportunities.

The interview delves into the critical intersections of workforce development and racial equity. Minson shares insights on systemic change, racial equity, and the evolution of leadership within the workforce development field. Through candid reflections, Minson offers a unique perspective on the challenges and opportunities for advancing equity in the workforce.

Tell us about Sandra Grace.

Sandra Grace is a change management consulting firm founded in 2020 with a vision to create an equitable and anti-racist talent development ecosystem. We primarily work with nonprofit organizations and nonprofit leaders in workforce development, assisting them in understanding racial equity and anti-racism and providing tools to disrupt inequitable practices, inequitable narratives, and inequitable policies.

I remember we first met on May 27, 2015 — the first day of the opening retreat of the Weinberg Sector Skills Academy in Baltimore. That was soon after another date stands out: April 19, 2015. What was the impact of that date on you as a workforce practitioner, as a Baltimore resident, and as a Black woman?

So that would be the day Freddie Gray was murdered. And it was really a mirror moment. It prompted introspection about my safety, the work I do, and the need for honest conversations about race and racism in workforce development. This moment forced me to confront the problematic framing of challenges faced by Black job seekers in Baltimore and fueled a commitment to addressing systemic injustices authentically and within the community. I knew that there were systems that were keeping people of color, and specifically Black people in Baltimore, stuck and excluded or limited in their access to economic mobility. I didn’t have all of the language and at the time, I wasn’t really comfortable having the conversation about the system of racism and its impact on the people we were working with every day as a direct service organization.

When you were in that Academy, you were working in direct program services at a training organization in Baltimore. When did you start focusing on systems change?

The Baltimore Academy was a Sector Skills Academy, so everybody there was leading some kind of sector-based training and working with employers in a particular sector. Mine was the maritime transportation, distribution, and logistics industry. I had to confront the question, “What is the system change that we’re trying to do?” We are trying to create a talent pipeline that increases the number of Black people and People of Color, or non-Black People of Color in Baltimore who are entering this industry. This was the first time that I really named that out loud. It was always the elephant in the room. Especially being a Black woman and an immigrant, walking into a very white and male-dominant industry, having to build relationships and then also create a space for the work that we were doing was really important. But it was in the academy — and when you asked the question, “What are the systems change efforts that you’re leading?” — that really made me acknowledge and then name explicitly the work that we were already trying to do.

A piece that you’d already written, “COVID-19 Revealed That Our Field Needs A Reckoning…”, happened to be published on the morning of May 25, 2020, right?

Yeah, other than it being the day after my daughter, my youngest daughter, was born, that day was the day, unbeknownst to many of us, that George Floyd would be murdered. So, we were navigating the pandemic for a few months and trying to figure out this “new normal.” I think it’s important to name that in the middle of all things COVID, starting in March, there were also these murders that were happening to Black-bodied people. So, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery, and then in May, George Floyd. And it was another mirror moment, a moment to lean harder into focusing on this intersection of racial equity and workforce development explicitly, intentionally, and with courage. I was feeling really frustrated with folks wanting to go back to business as usual, rather than seeing that there was an opportunity to really transform our systems. So, I put pen to paper because that was the only way I felt like I could get my message out to a broader audience.

Recently, I introduced you to some folks and I referred to you as “ the conscience of a field,” and you seem to be a little taken aback, but that’s how I acknowledge your impact. How do you acknowledge the impact that you’re having? When have you said, “Okay, this is what I’m meant to do”?

I don’t always acknowledge it. I was very taken aback when you said that. I think that’s a huge compliment, and there’s, I think, a weight, there’s a responsibility with that. Last year in particular, there were two frameworks that I had the opportunity to create that made me feel really proud. One was the Anti-Racist Workforce Development System Framework, developed in partnership with the Chicago Jobs Council, which put forth a set of visionary definitions for anti-racist program design and delivery, anti-racist policy design and implementation, anti-racist partnerships, and anti-racist client engagement.

And then in partnership with Jobs for the Future, the Fruit and Root Analysis framework, which provides practitioners with a way to examine themselves, their organizations, and their ecosystem to really see how they are uprooting root causes and leading to fruits of equity.

So those two, last year in particular, make me really proud and think, “Okay, I am making a difference, and this work is really doing what I feel called to do.”

What are some challenges for the development of leaders in this field?

The field has a long history of trying to engage with other players in the ecosystem who can help make sure that there are clear pathways and pipelines for folks who’ve been historically excluded and marginalized. I think there are some decisions that need to be made, or maybe there’s just more alignment, honesty and transparency about the continuum of change and where people enter that continuum. There’s a need for alignment and transparency about that continuum, from DEI to anti-racism, and everybody has a role they can play so there doesn’t have to be competition. We can partner and align with a common goal of making sure that historically excluded and marginalized workers have the best opportunity for economic mobility. And then at the individual leadership level, there’s just a lot more personal responsibility that folks need to take around the ways in which we’ve been complicit. How can we deconstruct our understanding of root causes, and then reimagine our role in particular as workforce leaders and practitioners so that we can realize those equitable outcomes and a more just society?

What are some tips that you would have for other leaders as they’re continuing to grow?

I think people need to be clear about the work they feel called to do and confident in doing that authentically. There’s a requirement for ongoing learning and commitment for personal professional development, deconstructing, reconstructing, and making sure that you give yourself space to do that learning and learning in community with other like-minded folks.

So a part of that would be to see the ways in which we’re already leading. It is also important to celebrate along the way, to center joy and rest for ongoing learning, and to surround yourself with people who can really support—authentically support—the journey in the way that you, Dee in particular, and Sheila have for years for me.

Conclusion

From confronting the realities of racial injustice to championing honesty, Minson’s story inspires a collective pursuit of equitable opportunity. Through her advocacy for authenticity, continuous learning, and supportive community building, she illuminates a path toward a more just, inclusive, and thriving workforce ecosystem.

Additional Resource:

The Reckoning Continues: 10 things Our Field Must Do

The 2025 Trustees Report projects that Social Security’s retirement trust fund will be depleted in 2033, triggering an automatic benefit...

If your bills feel unmanageable, you aren’t alone. Recent reports found that 30% of people are less able to afford bills today than they...

A comprehensive guide to 150+ essential multifamily real estate investing terms, from acquisition to disposition. A Absorption Rate The...