The financial frontier: Small business resilience in banking deserts

Throughout rural America, small business owners are facing a quiet threat: losing their last local bank. In rural towns, from North Carolina to Nevada’s frontier communities, a single local bank can mean the difference between convenient financial services and an hours-long drive for basic business transactions.

For small businesses in banking deserts, navigating capital access can feel like charting unfamiliar territory. According to organizations that serve small businesses, it takes a village of resources to support the financial success of rural entrepreneurs.

Banks often play a vital role in local economies, from innovatively serving consumers to driving small business growth. According to the Fed’s 2024 Small Business Credit Survey (SBCS), about 8 in 10 small firms use a bank as their primary financial services provider. Traditional banks also consistently serve as the main source of small business credit.

Small businesses create nearly half of US jobs. Small businesses create an even larger share of these jobs in rural areas. Rural businesses, their communities, and the economy rely on access to financial services.

Despite the demonstrated importance of banking relationships, recent declines in branch locations could leave small businesses with fewer options to access capital and build the financial connections critical to their survival. The Banking Deserts Dashboard can help quickly identify communities with few or no branches nearby.

While digital banking continues to advance, practitioners note that in-person services like meeting with local lenders remain irreplaceable. A recent St. Louis Fed study showed that despite stable demand, bank lending to small businesses declined between 2019 and 2023. Rural banking deserts also saw steeper lending declines than urban deserts. North Carolina, ranking third in the US for banking deserts, illustrates how small businesses still value these face-to-face banking relationships.

According to the latest data, six new banking deserts—areas with no bank branch nearby—formed between 2024 and 2025. Another 26 potential banking deserts – areas with just one branch nearby – formed during this time.1 This means 12.3 million Americans live in banking deserts and another 11.2 million live in potential deserts.

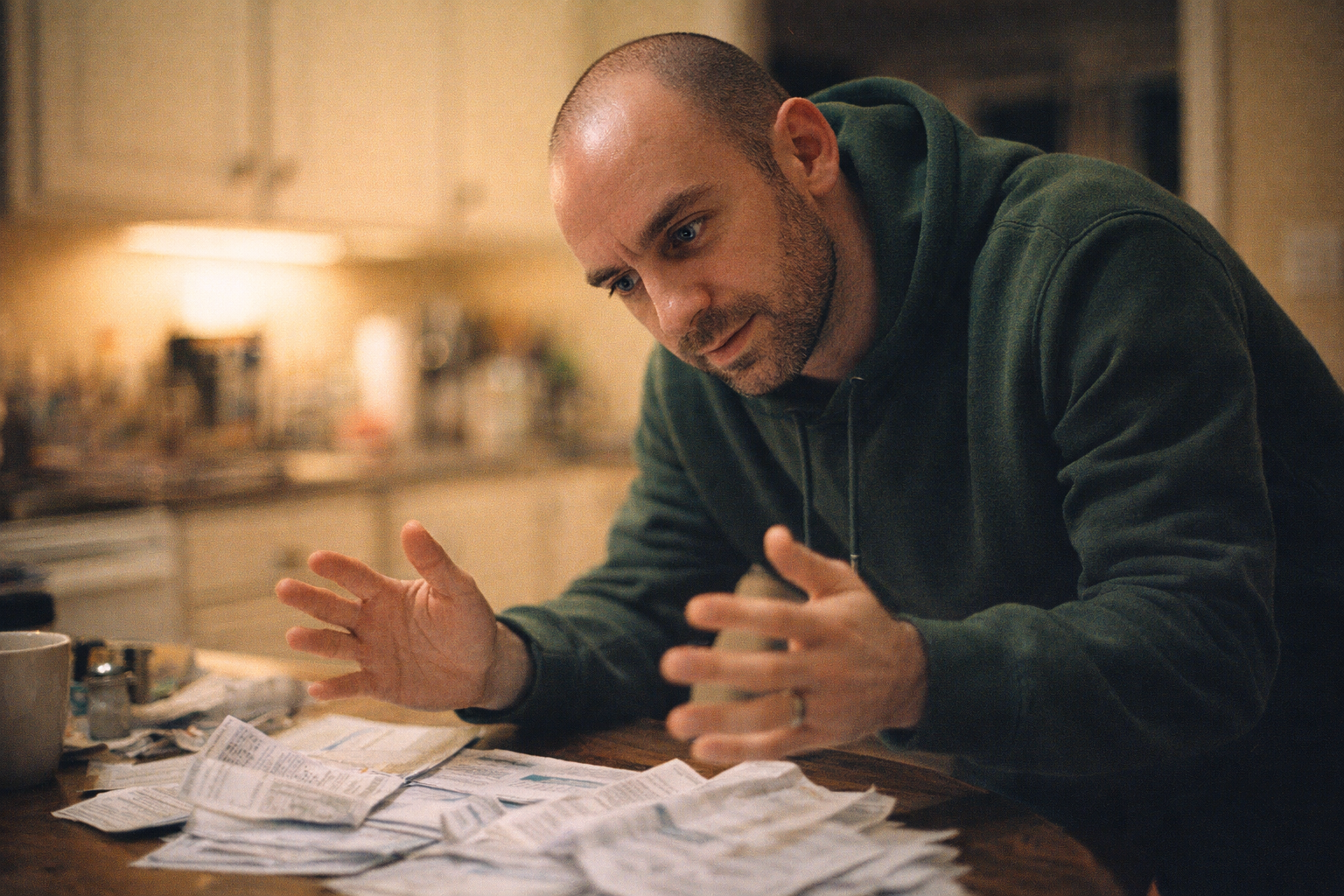

The relationship between banks and small businesses is essential. This relationship becomes even more apparent when communities face repeated economic challenges, as seen across rural North Carolina. The pandemic and several hurricanes have affected how rural small business owners access capital, according to Byron Hicks, executive state director at North Carolina’s Small Business and Technology Development Center (SBTDC).

“When small businesses go to a bank in person, they typically receive more favorable loan products. When you develop that relationship with your community lender, it’s usually a more favorable term sheet because the banker lives in that area. They know where the business is.”

Byron Hicks, executive state director, North Carolina’s SBTDC

“So many folks came out of COVID-19 with a Paycheck Protection Program loan to stay in business,” explains Hicks. “Then we were hit by Hurricane Helene and the flooding in the western part of the state. These people want to grow but don’t want to worry about any more money right now.”

When small businesses want to avoid more debt, SBTDC provides management counseling and technical assistance. For businesses that need financing, local banking relationships are critical.

“When small businesses go to a bank in person, they typically receive more favorable loan products,” Hicks says. “When you develop that relationship with your community lender, it’s usually a more favorable term sheet because the banker lives in that area. They know where the business is.”

The personal connection is particularly vital for small manufacturers in rural towns. “Some of these businesses are in metal buildings down a gravel road, you may not even know they are there,” describes Hicks. “These folks don’t ask for help. You must find them.”

Still, many North Carolina communities lack local access to in-person banking. The state has 268 banking deserts, representing over 10% of its census tracts.

According to Ariana Billingsley, deputy state director at SBTDC, rural branch closures can be far more than inconvenient. She warns that businesses seeking loans from distant branches can face an additional challenge: “That bank will likely require you to move your other accounts there before they issue a loan.”

This can create what Billingsley describes as a “vicious cycle” that gradually drains financial resources from small communities, leaving them with fewer lifelines when the next economic storm hits.

Many of the challenges faced by small businesses in North Carolina are evergreen in the high desert town of Tonopah, Nevada. Located about three hours between Las Vegas and Reno, Tonopah is a remote community of 2,000 people.

Tonopah was established during the 1900 silver rush. The town now balances its mining heritage with its modern tourism economy. Tonopah draws visitors to its distinctive landmarks such as the Clown Motel and the historic, reportedly haunted, Mizpah Hotel. Most local businesses are owner-operated with few employees and rely on tourism to sustain their restaurants, shops, gas stations, and hotels.

While Tonopah’s attractions are unique, its challenges mirror those of remote communities nationwide. In Nevada, 5% of census tracts are banking deserts and another 3% are at risk of becoming one if a local branch closed. Tonopah itself is in a potential banking desert with just one bank branch: Nevada State Bank. The next closest branch is a 2-hour drive away.

“Tonopah is the frontier. We’re way more rural than anybody thinks,” says Kat Galli, executive director of Tonopah Main Street. “We’re hours away from many services, whether it’s grocery shopping, banking, or medical care.”

For local business owners, the Nevada State Bank branch provides more than basic services like deposits and point-of-sale systems. Personal relationships with bank staff build crucial trust and support.

“We’re a very tight-knit community. We rely on each other, we all know each other well. This is a community member; they are one of us. That’s how they treat us as bank customers.”

Kat Galli, executive director, Tonopah Main Street

“We’re a very tight-knit community. We rely on each other, we all know each other well,” Galli explains. “This is a community member; they are one of us. That’s how they treat us as bank customers.”

Tonopah Main Street plays a central role in supporting the town’s small business ecosystem. “When people ask me about funding opportunities to start a small business, they usually go through Nevada State Bank,” Galli adds. “I think everybody likes being taken care of by people you know and have known for a long time.”

Sometimes these trusted relationships face practical limitations. 2024 SBCS data show a range of financing success rates for rural small businesses: 49% of those who apply at a large bank are approved for the full amount sought, compared to 64% at small banks. Many denials stem from insufficient collateral, low credit scores, existing debt, or low sales revenue.

“When someone wants to start a small business but has no securities, that’s when the bank sometimes isn’t the right lender,” Galli says. When traditional banking relationships reach their limits, rural communities must forge creative solutions to fill financial gaps.

When traditional lending is not an option, local banks can serve as connectors to alternative financing sources. “We get a lot of referrals from the Nevada State Bank Tonopah branch,” says Mary Kerner, CEO at Rural Nevada Development Corporation (RNDC), a community development financial institution (CDFI) serving rural Nevada communities.

With non-traditional criteria and more flexible terms, RNDC can make loans that traditional lenders find challenging. Kerner explains, “even if an applicant has no business collateral, we can take what they’re purchasing, like a backhoe or a floral van for deliveries, that would be used for business purpose. We have also utilized personal collateral.”

These innovative loans can create ripple effects through rural communities. “We’ve loaned money to medical professionals in medical deserts,” notes Joni Eastley, who serves on the boards for both Tonopah Main Street and RNDC. “If a doctor can’t obtain funding from a conventional lender to open an office, RNDC can help, benefiting not just that person but the community at large.”

Expanding on these creative financing models, SBTDC helps clients by blending traditional bank loans with community funding from Small Business Administration (SBA) programs, CDFIs, and local loan funds. “Very few small businesses have a 20% equity stake that they can put into traditional financing,” Hicks describes. “How can we help them mitigate some of the things that would traditionally get them a ‘no‘?”

Photo courtesy of SBTDC

For rural communities in Nevada and North Carolina, some of the most successful financing strategies emerge from strong partnerships where each organization focuses on its strengths. As Kerner explains, “We’re here to help. For businesses with credit issues, we’ll refer them to the Nevada small business development centers. They’re a huge partner. We look for more ways to make a deal work, not to turn it down. We can’t always help everyone, but we try.”

“We’re here to help. For businesses with credit issues, we’ll refer them to the Nevada small business development centers. They’re a huge partner. We look for more ways to make a deal work, not to turn it down. We can’t always help everyone, but we try.”

Mary Kerner, CEO, Rural Nevada Development Corporation

CDFIs like RNDC strive to help businesses become “bankable” through loans that can improve credit, collateral, and cash flow, creating a cyclical partnership with banks where referrals flow in both directions.

SBTDC emphasizes the importance of connecting entrepreneurs with the right financial partners based on their specific needs. “Banking is still relationship driven,” says Hicks. “We help them in each local market. Who’s lending in that area and that industry right now? Is that something that your local community bank has experience in?”

As rural communities navigate a new landscape of bank branch access, small businesses may rely more on relationships that connect resources like banks, CDFIs, development centers, and main street organizations. Hicks stresses that maintaining successful partnerships requires “keeping the dialogue going” and continued support for existing programs.

The local bank branch often serves as both the first point of contact and a trusted advisor. In regions where financial options are scarce, these branches remain a central pillar of rural small business ecosystems. For Hicks, this reinforces why banking will continue to be about relationships. “People go to folks they trust, who have been around, and will be here for the next 40 years,” Hicks explains.

In places like Tonopah and rural North Carolina, the future of small business resilience may depend not just on preserving access to financial services, but on strengthening the network of resources that sustain America’s small business frontier.

The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, the Federal Reserve System, or Fed Communities.

The biggest cause of fights between me and my beautiful wife, Mollie, over the years has been money. And the...

A Complete Stage-by-Stage Roadmap: With Every Top Resource Listed, Including Why Rod Khleif Is the Ultimate One-Stop Shop Apartment investing...

When Melissa looks back on the years leading up to her enrollment in National Debt Relief, one phrase stands out: ...