Beyond Boundaries – Vinegar Hill Magazine

by Kay Slaughter

“My position as art instructor involves using art to enhance self-esteem in students. Its uniqueness helps students realize that Black women are able to perform functions other than cooking, house cleaning, etc.” Alice Wesley Ivory, 1931-1999, Art Class Autobiography, 1988.

In the summer of 1957, after several years of teaching at Jackson P. Burley High School, the area’s segregated Black school, 26-year-old Alice Wesley headed off to the University of Wisconsin at Madison to work on a graduate degree in art education.

Nearby University of Virginia (UVA) was not the place for her, a Black female, although the courts had forced admission of two Black men into graduate programs in 1950 and 1951. Even so, Alice started her journey. breaking racial, gender, and economic barriers to become a renowned metal sculptor as well as a teacher of three decades.

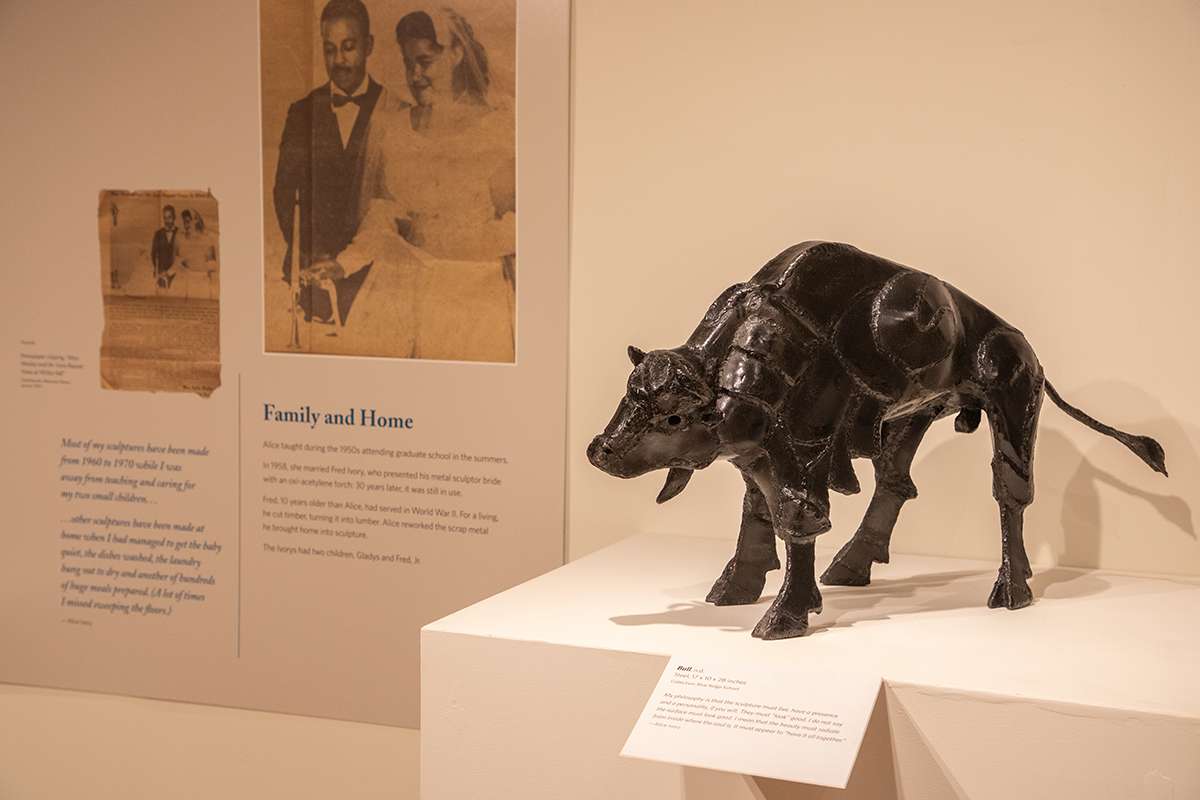

“Beyond Boundaries: The Sculpture of Alice Wesley Ivory” recounts her story and legacy in an exhibit sponsored by the Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society (ACHS) in cooperation with the Contemporary Gallery at Jefferson School African American Heritage Center (JSAAHC). The exhibit, open through mid-December provides an opportunity for new generations to learn about the life and times of this pioneering artist.

To find her creative path, Alice encountered many societal challenges as an African American female, but she also overcame obstacles by seizing the opportunities. Born in White Hall, Albemarle County, she grew up within a strong Black community grounded in nearby Mt. Olivet Church. Although her parents had no formal education, they were literate and hardworking, owning the family farm in White Hall.

The middle child of six, Alice walked two miles to attend elementary school; later, she rode a rickety bus for a long drive to Albemarle Training School near the current Ivy Creek Natural Area, the only high school for Blacks in the five-county area until Burley opened in 1951.

After graduation from Virginia State College (now University) an historic black college/university in Petersburg, Alice joined the art faculty at Burley. During her seven-and-half year tenure, she spent most summers at the University of Wisconsin, receiving her degree in 1962.

In 1958, Alice had married Fred Ivory, another Albemarle native, who presented his metal sculptor bride with an oxi-acetylene torch: 30 years later, it was still in use. Fred often picked up scrap metal for Alice to rework into her pieces. The Ivorys had two children, and after their early childhood, Alice taught for 20 years at Blue Ridge School for Boys, becoming its first art director and the first Black on the faculty.

Yet when she entered University of Wisconsin in her 20s, Alice was accepted only as a “provisional student,” considered likely deficient because of her southern education. She quickly proved her aptitude and talent, attaining student status without conditions.

Wisconsin became a life changing experience:

“I heard popping noises like small cannons exploding coming from next door. I peeked in and saw a group of young men waging a torch war, ” wrote Alice in her autobiography produced for an UVA art class two decades later.

With this encounter, she discovered what would become her lifelong vocation. She convinced a fellow student to show her some basics, and then prevailed upon her adviser, Leo Steppat, an Austrian immigrant and metal sculptor, to help her master the techniques of the acetylene torch.

Alice described creating her first large piece: the Boar:

“Word had gotten around to other classes; they wanted to see the woman make the pig. Almost every morning once it had a mouth, the Boar was fed an apple. I assumed that they came from generous classmates. . . . Leo Steppat refrained from bothering me. I would hear him mumble to himself as he went by, things like ‘Alice can really weld,’ ‘she’s a natural born sculptor,’ or ‘I’d give her three A’s if it were possible.’”

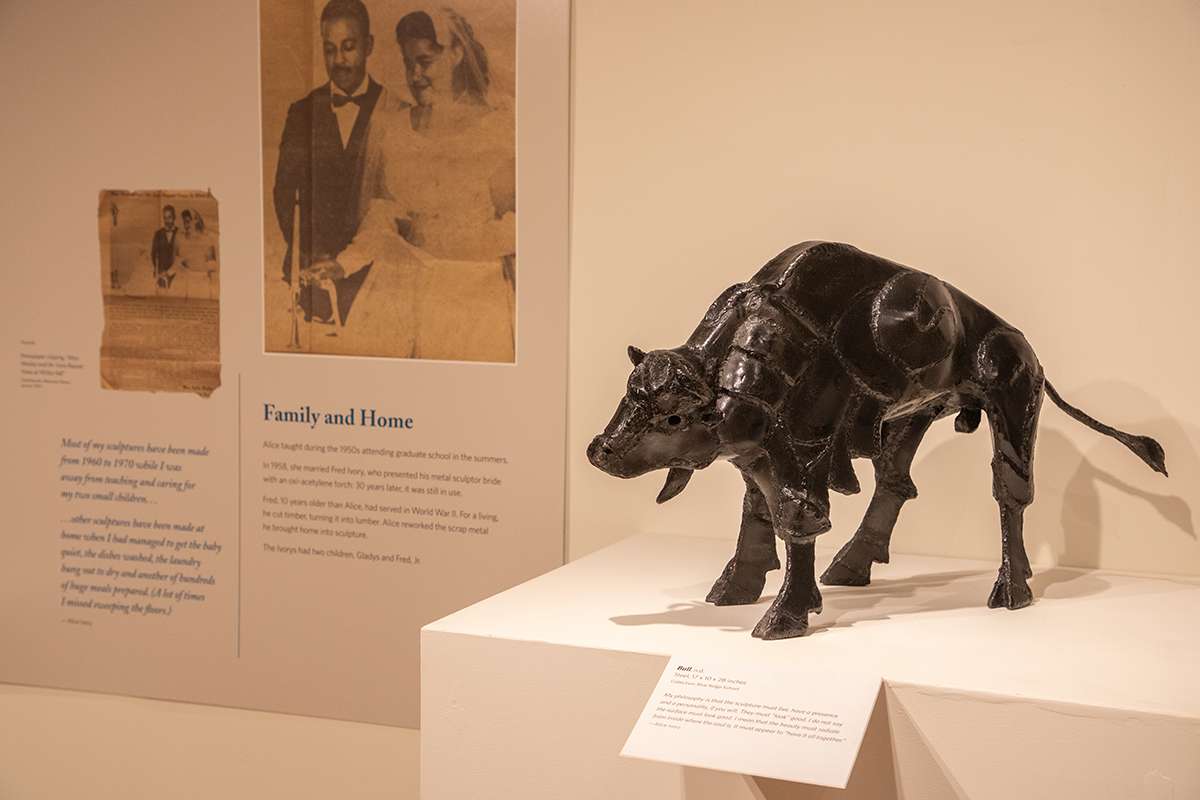

In the current exhibit, the art pieces depicting animals — including Great Blue Heron, Fish, Beetle, Bull — are accompanied by narrative panels recalling Alice’s personal odyssey and her views on education, religion, and art. The show features her work from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA) including Crow which won awards from the Museum. Another piece, Kangaroo, a mother with her “joey” in the pouch, was commissioned by the VMFA for a 1980 traveling exhibition allowing persons with vision problems and children to touch and feel the sculpture.

Exhibit panels feature photographs of two other works that were not physically present. Alice wrote about creating an outdoor fountain: “Turtle represents my first attempt at welding copper. It was commissioned by a person who wanted a piece of my sculpture. . . . Not knowing that copper is not usually welded, I assured the [owner] that I could do it in welded copper. . . . I consider it to be one of my best pieces. It is pictured at the water bin that was specifically constructed for it at the back of the owner’s residence. Incidentally, I had a live snapping turtle as a model, but the tail is designed for . . . [the sculpture]. I call the tail prehistoric.”

Another photographed work, The Eagle resides in Costa Rica. Its owner, the granddaughter of Charlottesville portraitist Frances Brand, accompanied her grandmother when she purchased Eagle and another sculpture in 1966, Dog, owned by the Brand Family. Dog is displayed in the gallery along with a portrait of Alice with these two sculptures. The portrait is among Frances’ collection of Charlottesville-Area “Firsts,” which included notable 20th-century figures who broke barriers of race, gender, and/or ethnicity. About her inclusion in this array, Alice noted: “I was pleased to have been chosen for one of Frances Brand’s Firsts.”

From her education at University of Wisconsin, Alice learned that metal forms should not look hard but need clean direct lines, and she focused on the form, rather than reproducing nature: “None of my sculpture is anatomically or biologically accurate. I sculpt things according to the mood I am in and base them on the way I feel about the subjects. The sculptures are not based on a love for the creatures. It is based on a love for beautiful form.”

VMFA had awarded certificates of distinction not only to Crow but also Wild Boar and Eagle I, exhibiting them in its galleries in the 1960s. The purchaser of Eagle I donated it to Virginia State University, where a relative viewed it in the 1970s, but the college currently has no record of it.

In 1967, VMFA hosted Alice’s one-woman show, and Charlottesville’s McGuffey Art Center and other local galleries also displayed her work. During her lifetime, Alice created more than 100 sculptures of animals, birds, fish, and insects. Since the exhibit’s opening, seven more sculptures have been identified.

The exhibit runs through December 14, open to school classes as well as other groups and individuals. Group tours should contact Jefferson School. The gallery is open Tuesday-Friday 1-6; Saturday, 10-12.

To reach teachers in public and private schools, ACHS worked with Annie Evans, education outreach director in historian Edward Ayers’ New American History Project to create a website:

https://resources.newamericanhistory.org/alice-ivory-breaking-boundaries

This exhibit was made possible through the generosity of the Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation, the Mental Health Fund of the Charlottesville Albemarle Community Foundation, the Charles Fund, Jefferson School African American Heritage Center Annual Fund and individual donors. The exhibit was collected, researched, and written by the Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society. It was professionally mounted by Andrea Douglas, curator of the Contemporary Gallery.

Kay Slaughter, member of the Board of the Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society and a lover of local history, was formerly mayor of Charlottesville and a member of City Council, 1990-98. She retired from practicing law at the Southern Environmental Law Center and researches and writes family history as well as essays about growing up in 20th-century Virginia.

Many people use their phones to handle everyday tasks, from scheduling appointments to staying connected with family. Budgeting apps are...

Parent PLUS borrowing will be capped beginning July 1, 2026: up to $20,000 per student per year and $65,000 lifetime...

Advisors affiliated with independent broker/dealers often assume that “independence” is a destination rather than a spectrum. Yet, when frustration creeps...